Bulky Goods: Paintings and Sculptures of Sarah D’Ambrosio and Morgan Hobbs By Augustus Hoffman

When I studied with the painter Graham Nickson, he had a term he used occasionally to describe a work of art. He would look at a painting, slowly, nod his head up and down, and then, after a pause, say, “This little painting here--it's really dense.” Then he moved on without further explanation, with a look on his face that said ‘surely my students know exactly what I mean’. Well, at first, I had no idea what he meant by calling attention to a painting’s density. Over time, I learned that describing something as dense was one of Nickson’s highest praises. A dense work of art, for Nickson, possesses the weightiness of the creative process; the fresh starts, dead ends, late nights, and brief moments of clarity that comprise the act of making. A dense piece might display physical attributes that are dense, such as the impasto mark making of a Rembrandt portrait or a Joan Mitchell landscape, but work that is truly dense extends beyond its physical attributes andinfiltrates a type of metaphysical realm. It is artwork that shows the viewer the struggle of creation, not as a schematic roadmap or aesthetic endpoint but rather as a messy archive, an unfathomable map of past, present and future marks all colliding and dancing with each other until they ultimately find synchronicity outside of their temporal framework, doing so in a way that is impossible for the creator to entirely plan.

I think of Sarah D’Ambrosio’s and Morgan Hobbs’ work as being bulky, much in the same way Graham Nickson would praise some work as being dense. At first glance, this comparison might feel like a stretch considering the different subject matter of both artists’ work; D’Ambrosio focuses primarily on paintings of saunas and bathhouses with the male nude (or almost nude) as her preferred subject matter, exploring the physicality and intimacy of the male body. Hobbs moves between painting, sculpture, and painted reliefs, developing an artistic language that is archeological in its nature, excavating a connection between invoked historical artifacts and our present selves. There are physical attributes to both of these artists’ work that warrant the use of bulky as an adjective in describing them which I will get into later. In my opinion, describing a work of art as bulky carries deeper qualities beyond physical attributes; there is something activating about things that are bulky. Their life force bubbles up from within and forces itself upon the outside world. Bulky things push up against, crowd out, bulge towards a very proper, perhaps trim understanding of how we organize the world. Things that bulk take up too much space, they carry in themselves, in their very existence, an affront towards an assumed hierarchy of how objects and categories are supposed to exist.

Sarah D’Ambrosio, Parachute Jump, oil on canvas, 48 x 34 inches.

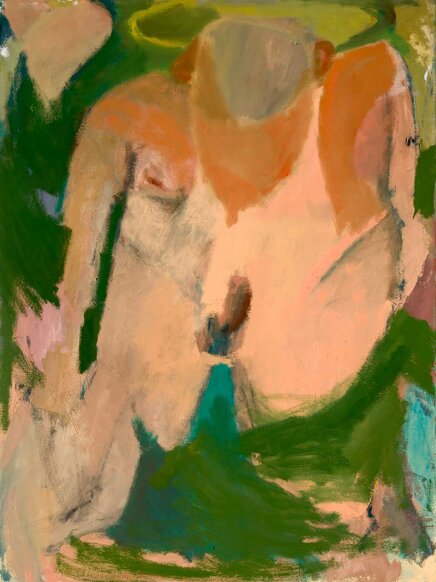

D’Ambrosio’s figures, mostly male, are made from distorted bulky masses that present themselves as being distinctly separate from, but fundamentally tied to their natural environments. Their tense forearms, crouching legs, and forlorn faces all seem to have fought their way into existence; forms that are strong enough to distinguish themselves against richly colored pinks, yellows, pale greens, orange, and deepsea blues that comprise undefined color masses—past decisions which might have led to some recognizable forms that instead never came to fruition. D’ambrosio’s process is methodical, ruthless even, and as a result everything we witness is hard fought over; these figures hulk their way into existence, pulling themselves out of the primordial soup that is wet on wet painting. Few paintings depict this quite as well as Parachute Jump.

D’Ambrosio’s figures, mostly male, are made from distorted bulky masses that present themselves as being distinctly separate from, but fundamentally tied to their natural environments. Their tense forearms, crouching legs, and forlorn faces all seem to have fought their way into existence; forms that are strong enough to distinguish themselves against richly colored pinks, yellows, pale greens, orange, and deepsea blues that comprise undefined color masses—past decisions which might have led to some recognizable forms that instead never came to fruition. D’ambrosio’s process is methodical, ruthless even, and as a result everything we witness is hard fought over; these figures hulk their way into existence, pulling themselves out of the primordial soup that is wet on wet painting. Few paintings depict this quite as well as Parachute Jump.

Sarah D’Ambrosio, Seaweed Boy at Coney Island, oil on canvas, 56 by 48 inches.

But to be clear, despite their direct, even muscular application, these paintings are not brutish. In Seaweed Boy at Coney Island, for example, we see this bulging muscular figure in a state of privacy and real intimacy. There is a sensitivity to his expression which suggests that D’ambrosio is not so much commanding her paintings to exist a certain way but rather is asking them where they want to go. The real strength in D’Ambrosio’s practice is her ability to be scrupulous, severe at times, with an appropriate amount of vulnerability too. Her paintings are in a constant state of discovery, both for us the viewer but also the artist as well and it’s clear how much delight she takes in this process. However, we also get a sense that D’Ambrosio will strike these men down if they become too unwieldy, too greedy in the space they take up. And so they exist in a type of temperamental, fragile paradise ever on the verge of becoming.

But to be clear, despite their direct, even muscular application, these paintings are not brutish. In Seaweed Boy at Coney Island, for example, we see this bulging muscular figure in a state of privacy and real intimacy. There is a sensitivity to his expression which suggests that D’ambrosio is not so much commanding her paintings to exist a certain way but rather is asking them where they want to go. The real strength in D’Ambrosio’s practice is her ability to be scrupulous, severe at times, with an appropriate amount of vulnerability too. Her paintings are in a constant state of discovery, both for us the viewer but also the artist as well and it’s clear how much delight she takes in this process. However, we also get a sense that D’Ambrosio will strike these men down if they become too unwieldy, too greedy in the space they take up. And so they exist in a type of temperamental, fragile paradise ever on the verge of becoming.

Sarah D’Ambrosio, Coney Island Angel, oil on canvas, 40 x 30 inches.

There is another way in which these paintings feel bulky, too. The reader doesn't need to be reminded that the cemetery of art history is littered with countless gravesites of female nude paintings. Most of these women possess a body of a certain type, created almost entirely under the eager eye of their male creators. But here comes D’Ambrosio’s men, painted under female scrutiny, bulky in their presence, uncomfortably pushing against a male gaze that has become ubiquitous with the story of art.

There is another way in which these paintings feel bulky, too. The reader doesn't need to be reminded that the cemetery of art history is littered with countless gravesites of female nude paintings. Most of these women possess a body of a certain type, created almost entirely under the eager eye of their male creators. But here comes D’Ambrosio’s men, painted under female scrutiny, bulky in their presence, uncomfortably pushing against a male gaze that has become ubiquitous with the story of art.

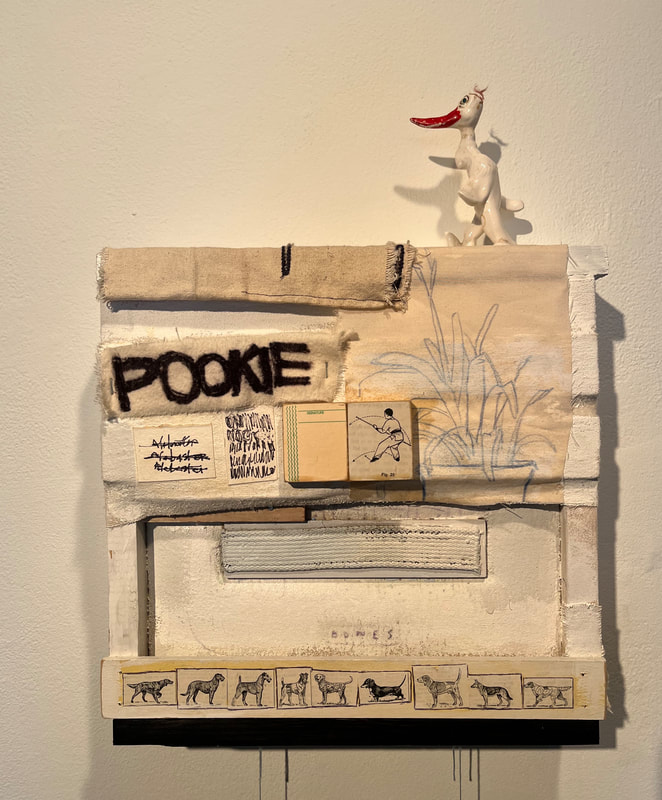

Morgan Hobbs, Brick by Brick, oil and acrylic on papier mache and recycled materials, size variable.

Morgan Hobbs’ current work, made up of precariously placed papier-mache sculptures, vertigo inducing reliefs, and wobbly painted mosaic tiles, conjures an archeological site for remnants of a civilization that is both past and present, familiar and unknowable. There is a subtle disorientation we experience taking in relief pieces such as City Hall that place our relationship to it in a type of unspecific limbo, a permanent dolly zoom, that fosters a distinct feeling that our relationship to these objects will remain and perhaps grow indeterminable over time. Take Circumpoint (Study 2) as another example: what at first appears to be a black and white mosaic painting perhaps of some ancient ritual site soon morphs into a present day QR code. Hobbs’ work begs the question: Are we examining the remnants of an unfathomable past or are we actually staring down at our phones? The regenerative quality of Hobbs’ work is her ability to genuinely and deliciously answer “yes.”

Morgan Hobbs’ current work, made up of precariously placed papier-mache sculptures, vertigo inducing reliefs, and wobbly painted mosaic tiles, conjures an archeological site for remnants of a civilization that is both past and present, familiar and unknowable. There is a subtle disorientation we experience taking in relief pieces such as City Hall that place our relationship to it in a type of unspecific limbo, a permanent dolly zoom, that fosters a distinct feeling that our relationship to these objects will remain and perhaps grow indeterminable over time. Take Circumpoint (Study 2) as another example: what at first appears to be a black and white mosaic painting perhaps of some ancient ritual site soon morphs into a present day QR code. Hobbs’ work begs the question: Are we examining the remnants of an unfathomable past or are we actually staring down at our phones? The regenerative quality of Hobbs’ work is her ability to genuinely and deliciously answer “yes.”

Morgan Hobbs, City Hall, oil and papier mache on panel, 8 x 8 x 2 inches.

There is a bulky quality to Hobbs’ work—less noticeable at first than D’ambrosio’s—a subtle physical exaggeration that initially comes to us in a murmur but speaks up the longer we spend with her pieces becoming even louder and more distinguished when we try to conjure her work from memory. Looking back at photos of her sculpture Brick by Brick: Worth & Weight, I’m surprised to discover that this type of exaggeration isn’t as pronounced as I remember it. But it is there surely, both in physical form and perhaps more importantly, as a memory or ghost of my past understanding of it. Made from discarded Amazon boxes, covered in pulpy, papier-mache, we are presented with a stack of literal building blocks for some unnamed ancient civilization. Each block is porous, with a subtle shift in texture and color, slightly engorged as it butts up next to, leans against, or rests atop its neighbor. These pieces feel a bit unwieldy, even awkward, as they ascend towards the heavens. Their assembly is both playful and precarious; perhaps they reach towards some future utility or perhaps they are the aftermath of a previous collapse. Either way, the membrane that neatly separates our comprehension of past, present or future becomes permeable, even non-existent the longer we take in Hobbs’ work .

There is a bulky quality to Hobbs’ work—less noticeable at first than D’ambrosio’s—a subtle physical exaggeration that initially comes to us in a murmur but speaks up the longer we spend with her pieces becoming even louder and more distinguished when we try to conjure her work from memory. Looking back at photos of her sculpture Brick by Brick: Worth & Weight, I’m surprised to discover that this type of exaggeration isn’t as pronounced as I remember it. But it is there surely, both in physical form and perhaps more importantly, as a memory or ghost of my past understanding of it. Made from discarded Amazon boxes, covered in pulpy, papier-mache, we are presented with a stack of literal building blocks for some unnamed ancient civilization. Each block is porous, with a subtle shift in texture and color, slightly engorged as it butts up next to, leans against, or rests atop its neighbor. These pieces feel a bit unwieldy, even awkward, as they ascend towards the heavens. Their assembly is both playful and precarious; perhaps they reach towards some future utility or perhaps they are the aftermath of a previous collapse. Either way, the membrane that neatly separates our comprehension of past, present or future becomes permeable, even non-existent the longer we take in Hobbs’ work .

Morgan Hobbs, Circumpoint (study 2), oil on panel, 12 x 12 inches.

The bulkiness of Hobbs’ sculptures exists not just in its physicality but in its ability to lodge itself in our psyche, pushing up against the clean categories we use to demarcate, comprehend, and categorize time. Its presence, at first subtle, grows and nags at us the more we try to understand it. Similarly, the bulkiness of D’Ambrosio’s men, painted in a pronounced, overtly direct way, do not elicit feelings of repulsion, overcrowding, or intimidation—rather, the opposite occurs. Her forms feel vulnerable, intimate and at times ethereal. D’Ambrosio is capable of turning the painted nude into an expansive, ephemeral landscape. At times I forget the genre of the paintings I’m looking at. Rosy flesh tones are more likely to mimic the fleeting, slanting light on the side of a mountain as opposed to the network of dense human muscles they actually depict. And here I think is where the artworks of D’Ambrosio and Hobbs present themselves to us as a gift. What at first feels too bulky is actually pointing us towards our own thin assumptions about how and where to elicit meaning in art. Artifacts we initially cast to the ancient realm reveal themselves to carry the ubiquitous weight of our present day consumerism. Men who at first glance feel intimidating in their muscular demeanor expose a vulnerability and openness we are surprised to find in depictions of masculinity. In the end, these things that are called bulky take up exactly the right amount of space.

What more could we really ask for from a work of art?

Bulky Goods will be on view at the Front from March 9th through April 7th.

The writer would like to thank Hannah Richter and Ben Saxton for help in editing this piece.

The bulkiness of Hobbs’ sculptures exists not just in its physicality but in its ability to lodge itself in our psyche, pushing up against the clean categories we use to demarcate, comprehend, and categorize time. Its presence, at first subtle, grows and nags at us the more we try to understand it. Similarly, the bulkiness of D’Ambrosio’s men, painted in a pronounced, overtly direct way, do not elicit feelings of repulsion, overcrowding, or intimidation—rather, the opposite occurs. Her forms feel vulnerable, intimate and at times ethereal. D’Ambrosio is capable of turning the painted nude into an expansive, ephemeral landscape. At times I forget the genre of the paintings I’m looking at. Rosy flesh tones are more likely to mimic the fleeting, slanting light on the side of a mountain as opposed to the network of dense human muscles they actually depict. And here I think is where the artworks of D’Ambrosio and Hobbs present themselves to us as a gift. What at first feels too bulky is actually pointing us towards our own thin assumptions about how and where to elicit meaning in art. Artifacts we initially cast to the ancient realm reveal themselves to carry the ubiquitous weight of our present day consumerism. Men who at first glance feel intimidating in their muscular demeanor expose a vulnerability and openness we are surprised to find in depictions of masculinity. In the end, these things that are called bulky take up exactly the right amount of space.

What more could we really ask for from a work of art?

Bulky Goods will be on view at the Front from March 9th through April 7th.

The writer would like to thank Hannah Richter and Ben Saxton for help in editing this piece.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed